Photo by Chris Hatcher

When visiting Peter Krasnow: Breathing Joy and Light, take time to appreciate the music playing in the gallery. LA-based DJs Alejandro Cohen and Mark “Frosty” McNeill of internet radio station dublab worked with Skirball curator Laura Mart to create a custom soundtrack just for the exhibition.

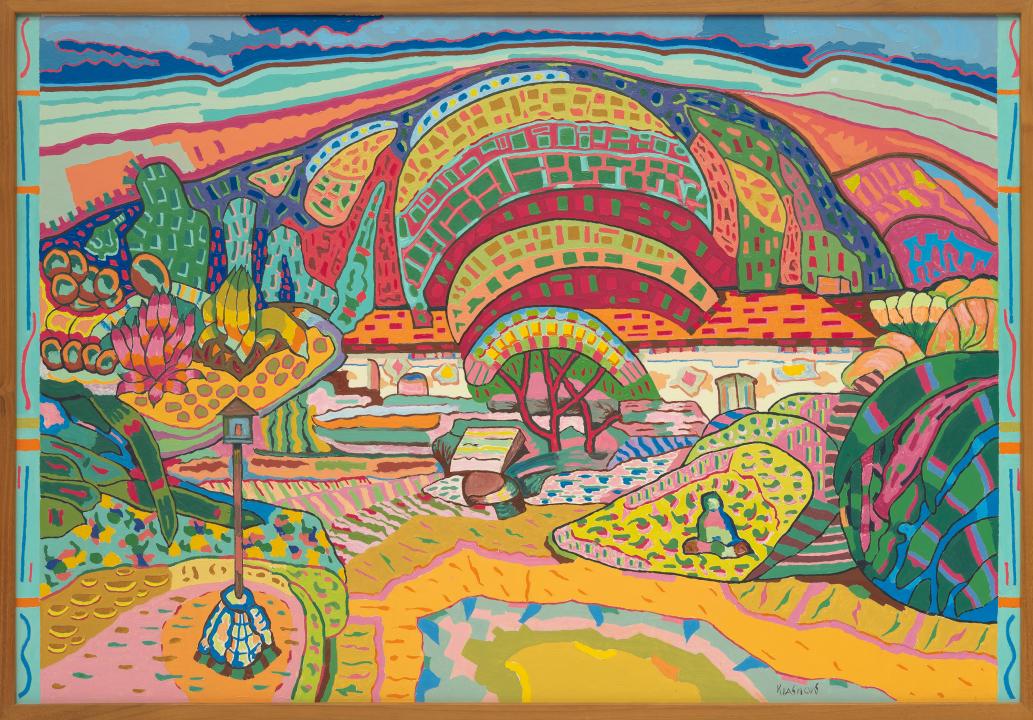

This carefully considered collection of songs weaves various threads of Peter Krasnow’s character and sources of artistic inspiration. Within this audio offering, Krasnow’s interest in Jewish mysticism mingles with music evoking the lush landscape of his beloved garden; recitations of sacred Hebrew texts are intertwined with Jewish Ukrainian folk songs; and transcendent tonal compositions flow alongside nature sounds. By pointing to the multilayered references that coexist in Krasnow’s paintings, this musical collage aims to prompt a deeper engagement with the artwork on view.

Mart sat down to talk with Cohen and McNeill to discuss how the songs were selected and the fascinating stories of many of the musicians featured, including Charlie Chaplin, Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou, and Henry Cowell.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

LAURA MART: The title of the exhibition, Peter Krasnow: Breathing Joy and Light, was one of the guiding elements of our collaboration. How did you translate that concept of “breathing joy and light” into a musical sensibility?

MARK “FROSTY” MCNEILL: It’s been a running theme—light—as it’s tied to creativity and joy and wonder, and the specific light of Los Angeles. It’s so unique.

[When I was working on this] I was trying to imagine Peter Krasnow being an artist who was not born here and then lived in various places in the United States and then came to Los Angeles. I tried to think of what his impression was of the light. Some artists are so attuned to their environment. I was trying to imagine Peter in his garden seeing the light move through that space—seeing how it shifts in the day, seeing how light sets a glow on a subject.

We all know the golden hour of Los Angeles and how magical it is. So that was something I was trying to envision … how a visual artist might find some resonant energy in that light and that landscape, and then thinking of how, musically, that can be reflected. It’s often not a one-to-one analogue, but it’s attempting, much like light, to reflect this idea of what’s happening. That was really the idea in the music: to get that glow going.

ALEJANDRO COHEN: I read about his work before I saw it, or—not so much his work, but his biography. So, I painted a picture in my head first of what that might have been like. I started [looking at] his work and it struck me as something I could identify with.

What is the feeling of coming to Los Angeles? I originally came under very different circumstances, but I came to Los Angeles, as well, as an adult. I was focused on expression, the idea of inventing yourself and the opportunities the city provides for that.

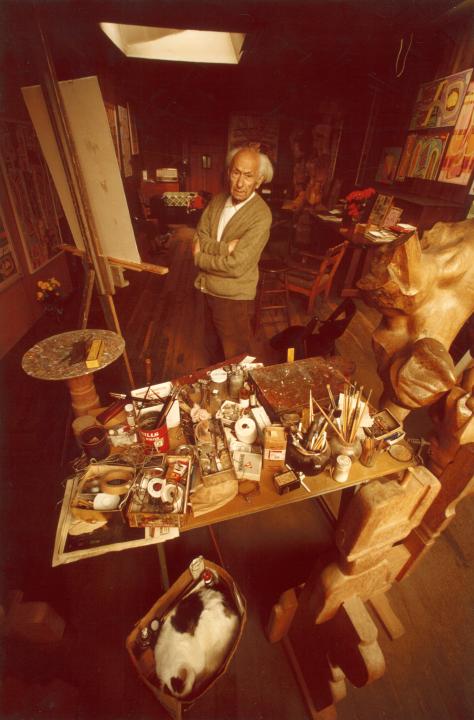

LM: I think the subjectivity that you bring to it is really interesting. That’s one of the things I like about the soundtrack is that it has an imaginative and creative aspect. It’s not, “Well this is literally what he listened to,” and part of the reason why we don’t know that is because Krasnow is a massively understudied artist. He’s somebody who was somewhat reclusive during his lifetime. He avoided publicity, he really wanted to do his own thing, and he didn’t like what critics said about his art. He didn’t like being compared with other artists or movements or styles. He had professional contacts, but he didn’t cultivate them in the same way that other artists who were more conventionally successful or well-known did.

“The subjectivity that you bring to it is really interesting. That’s one of the things I like about the soundtrack is that it has an imaginative and creative aspect. It’s not, “Well this is literally what he listened to.”

AC: There are a few artists who I thought to include, outsider artists, people who really forged their own way and did their own thing and existed in their own world … I don’t think any of them ended up making it, you know, but it’s just funny. It’s funny that you say that about him. I didn’t know about his being more reclusive and not kind of “playing the game,” in a way. But he also struck us that way.

LM: Were there any musicians you did include who have a similar independent spirit or ethos? One of the things I noticed about Krasnow was that he lived in New York, and then he moved to California because he didn’t like New York. He specifically rejected everything it represented at the time. You know, it was the expected place for an artist to live, it was where you could be a part of the “in” crowd, it was where you could find patrons who would commission you to paint what they wanted you to paint, not what you wanted to paint. And so, he set out for California so that he could be inspired by the landscape. So that he could live and work outside the influence of what he perceived to be this narrow-minded conception of what an artist’s life could be.

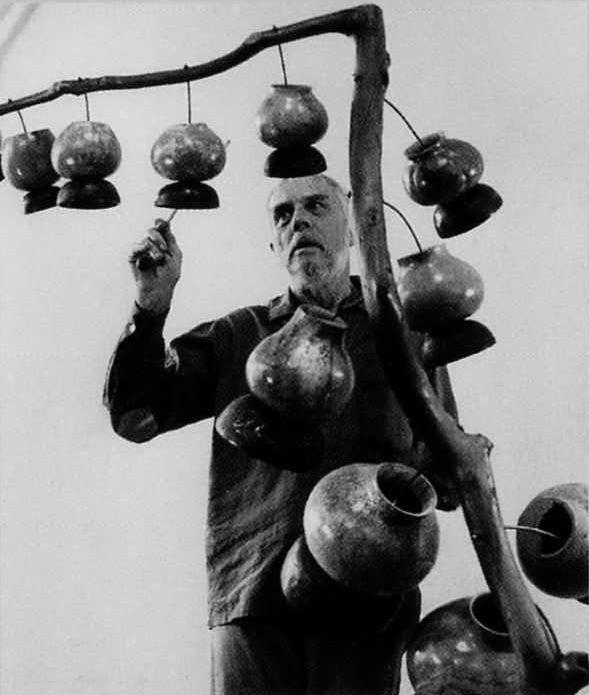

AC: Yeah, someone like Harry Partch strikes me as someone with a similar spirit. Partch went on to create his own tunings and built his own instruments, not even going with conventional instruments.

Images courtesy of HorsePunchKid, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Images courtesy of HorsePunchKid, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Images courtesy of HorsePunchKid, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

MFM: Lou Harrison, as well, was considered one of these West Coast mavericks who created his own versions of the gamelan [the traditional Indonesian percussion orchestra]. Henry Cowell, too; a lot of these artists were maverick composers.

Also, the very first artist on the offering, Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou, who just passed away on March 26. She came from a very wealthy family in Ethiopia and through many different twists and turns ended up joining an Ethiopian Orthodox convent in Jerusalem. She was someone who was feeling religious persecution, but she was also carving out her own path, separate from her background, and created a form of music that is still slowly being unraveled and being notated. In fact, Amanda Petrusich, who is one of my favorite writers, said that when Emahoy was playing, it sounded like she had ears on the end of each fingertip.

AC: The other one that I thought of is Charlie Chaplin who also has a similar path to Peter Krasnow’s. He is an immigrant who came from a dark place or a dark time in Europe and then reinvented himself in Los Angeles, and really embraced the city and built his own world here—obviously with a different degree of success. But still I think there’s something to be said about that, and that’s why I included the song “Smile” by Charlie Chaplin.

LM: It might not be obvious looking at Krasnow’s work, but he was very interested in the movie industry, especially in the 1920s, and he was friends with filmmakers like Oskar Fischinger.

One of the things that I appreciate about many of the tracks on the musical offering is that they use really complex and unusual creative rhythmic or tonal structures. That, musically, echoes what I see visually in Peter Krasnow’s paintings, which are also unusual in the way the visual elements are structured according to his own logic.

MFM: Krasnow had a unique way of approaching art, in a way using elemental materials. I think that Krasnow’s work isn’t flashy and gimmicky, but it’s using elemental materials to make something supernatural in a way.

LM: Yeah, he used paint straight from the tube, he only added black and white to mix his colors.

MFM: Many of these artists, even if they’re using electronics, they are in a way channeling the organic as well as the supernatural in what they do. I’m always fascinated by people who use the raw material of the world to create something that goes beyond it.

LM: To me, one of the most surprising elements of this soundtrack was hearing these amazing works that have deep roots in Jewish mystical spirituality, but also feel very much like New Age music. It feels like meditation music, in a way that I often associate with the chanting of mantras in Hinduism or Buddhism, things that come from the Western adoption of Eastern spiritual practices. That’s what I mean by "New Age,” the New Age spirituality movement from the 1960s to the present. To me, that’s a very California thing. There are a lot of spiritual seekers, like you mentioned earlier, in California.

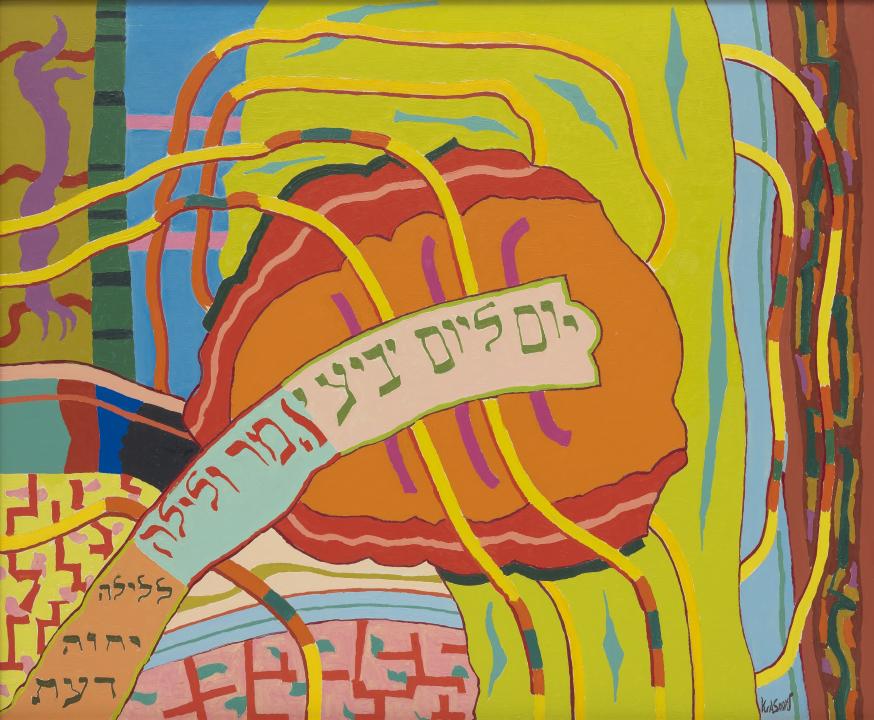

In terms of the tracks that have specific connections to Krasnow’s work, I’m thinking of Steve Reich’s “Tehilim I” which incorporates the same text from Psalm 19 that Krasnow uses in one of his paintings. That’s one of the direct one-to-one moments of connection that I thought was really cool and special. I also really loved the track, “YHWH Osenu” from the album Sacred Name, Sacred Code by JJ and Desiree Hurtak and Steven Halpern.

“In terms of the tracks that have specific connections to Krasnow’s work, I’m thinking of Steve Reich’s ‘Tehilim I’ which incorporates the same text from Psalm 19 that Krasnow uses in one of his paintings. That’s one of the direct one-to-one moments of connection that I thought was really cool and special.”

MFM: Yeah, JJ Hurtak is someone I got connected to through Alice Coltrane because they were friends. There’s this album of his that never came out called Sacred Language of Ascension. It used both Hebrew chants and Vedic chants and was based on the idea, in both spiritual practices, of recitation of the name of God. That’s very important, repetition. It’s something that came up when you mentioned Steve Reich, who is part of the minimalist school. For the minimalist composers that practice [of repetition] is similar to the idea of the recitation of the names of God in scripture, and it is very connected to very early spiritual states, trance states, which are also connected to our relationship to nature and the patterns of nature. It’s sort of like formal religion has its roots in these natural and supernatural mystic practices.

So, with the work that we included, in many ways they are prayers, not just lyrics to a song, they’re communication to a holy spirit or to a sacred space. And so, it’s a fully different intentionality and energy that you get.

LM: Yeah, absolutely. I was fascinated by the Hebrew phrase, YHWH Osenu or Yod-He-Vod-He Osenu. I looked this phrase up to see what it means. So, YHWH is the name of God in Hebrew, which you don’t pronounce when you read it. But, YHWH Osenu, means “God our maker” or “the creator.” So, it’s about making and creativity, which I think is particularly appropriate when looking at Krasnow’s art and spirituality.

Something that I think really speaks to Krasnow’s interest in storytelling from global cultures is the idea of archetypes It’s a concept that comes from the work of Carl Jung. That was something that Peter Krasnow read and was influenced by. When he was writing his autobiography in the late 1960s, it was very much something that was on his mind. It came up again and again.

I found out from his correspondence with one of his friends, Grace Clements, who was a writer. She was very interested in these [ideas about archetypes], and through her, Krasnow became interested in these repeating elements of the human psyche—whether that’s in the individual psyche, or a collective psyche of a group, or of a civilization.

So, he read Jung, he read The Secret of the Golden Flower, and he also loved The Little Prince. I know there’s the literal connection with The Secret of the Golden Flower which is also the title of one of the tracks.

MFM: Henry Cowell was one of the major figures pushing through the idea of “musics of the world,” Lou Harrison, also. Harry Partch, too. And they were all in conversation.

Henry Cowell worked a lot for Folkways Records, hosted a radio program, produced albums of music from around the world, and also was using these [global] instruments in his work. He is also someone who had a desire to create beauty out of dire circumstances and to be very forgiving, in a way. You know, he was imprisoned for being a homosexual, in San Quentin. While he was in San Quentin, he was ostracized by many composers, but he remained really connected to the ones who got him and understood what an injustice it was. [In prison], he was teaching music; he was so giving in that space of incarceration.

“[Henry Cowell] was imprisoned for being a homosexual, in San Quentin. While he was in San Quentin, he was ostracized by many composers, but he remained really connected to the ones who got him and understood what an injustice it was. [In prison], he was teaching music; he was so giving in that space of incarceration.”

Henry Cowell playing the piano. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of composer Lou Harrison. Harrison House, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Harry Partch with his gourd tree. Unknown author, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

LM: I’m not sure I had found this out when we talked at the beginning of our collaboration, but speaking of Henry Cowell, Peter Krasnow actually threw a party for Henry Cowell in the 1920s. [Cowell] was one of the connections he met through Edward Weston, or he met through someone else in their artistic circles. I think the description was in Krasnow’s diary or in Weston’s diary, it said something along the lines of “we had a party for a composer who made music solely out of pots and pans” and that was determined to be Henry Cowell.

One of the other really significant pieces of Krasnow’s life, of course, was his heritage and his immigration experience; having been born in Ukraine while it was under the control of the Russian Empire, at a time when antisemitism was rampant and persecution against Jewish communities included pogroms.

I love that you included some Ukrainian Jewish music that feels very much of a time and place. Do you have any light that you can shed on those selections?

MFM: I mean, if you’re looking at Ukrainian Jewish music, looking at the numbers … As you mentioned, the antisemitism, pogroms … I was reading about the history, and I think that these communities had to be bonded for survival. Music is such a part of these community rituals around the world —whether it’s a wedding, a birth, a birthday, a funeral, et cetera. [It was] also a time and a place where a lot of people weren’t listening to music at home as much. There was a burgeoning record industry in the ’20s, but it wasn’t so common that everyone had a phonograph. You might have [music] more in a communal space.

I’m a believer in that, like, cultural DNA, ancestral DNA … in a way that even if you’re not thinking about it, it’s encoded, you know? And so, I think that some of this music might have been part of that space and, like, ingrained in his psyche.

“There was a burgeoning record industry in the ’20s, but it wasn’t so common that everyone had a phonograph. You might have [music] more in a communal space. I’m a believer in that, like, cultural DNA, ancestral DNA … in a way that even if you’re not thinking about it, it’s encoded, you know?”

There’s an artist who we included, Nikolai Kapustin—and that’s more of the sort of experimental jazz, [with a] classical interpretation—he was of Russian-Jewish descent, born in Ukraine, but in Soviet Ukraine. So that was a way to tie [Ukrainian Jewish heritage into the soundtrack]. Also, [he was] somebody who was also trying to innovate through their art—their work—especially as his career progressed. He was born in 1937 and I imagine that—maybe like Krasnow too, sort of—there's a point, I think, in your life, especially when you’re young, you’re sort of moving away from your roots and then later, you’re kind of reflecting on them and embracing them. A lot of his music interpreted and examined these Jewish themes.

So, it was interesting to be able to include [Kapustin’s] work. He was actually totally new to me, but again, that’s the fun of these things: getting turned on to new art and music and artists and stories. I always like this sort of web of connection. If you were to reveal more and more, you’ll find that all of these things are much more interconnected than we imagine.

LM: So many things to respond to there. One, the wedding. There’s a literal depiction of a wedding in the exhibition. That’s the earliest drawing that survives that Krasnow made when he first immigrated to the US. In it, he depicts a wedding scene on the streets of his hometown. The work is a drawing on paper, it’s called Chupa. It’s very modest, graphite on paper, made before he had formal artistic training. He includes the wedding scene: the bride, the groom, the chupa canopy, but there are also musicians who are playing. There’s a cello, or maybe it’s a bass, anyway, it’s big. So, music was for sure a part of his life. This kind of detective work, this guess work, is interesting. These were communities that didn’t have a lot of resources to do things like record their music or even necessarily to notate things, and a lot of folk music, of course, is oral tradition, living tradition. When those communities were wiped out, first by pogroms and then by the Holocaust, a lot of that was lost, a lot of that living tradition was destroyed.

And so, to see the way that some of it was preserved—in that contemporary composers are picking up some of those roots—I think it really speaks to this idea of rebirth, which is a major theme of the exhibition, rebirth after death and new life after destruction.

MFM: I think that putting these people side by side that you might, from the outside, not group together, [you see that they] have an affinity, have these deep connections. I think of William Grant Still, who we included—an African American composer—his piece “Summerland” from Three Visions. Three Visions was a suite all about death and rebirth and the afterlife and about dreaming, dreaming of heaven. William Grant Still’s piece was from 1935, and he was born in 1895, so he and Krasnow were [alive] around the same time. Grant Still [also] was very active here, and died in Los Angeles in 1978. So, you know, they could have even crossed paths here, but are coming from different spaces.

There’s a thing that Alice Coltrane says—it's sort of a common phrase—“The paths are many; the destination one.” And so it is fun to place people side by side and contextualize or recontextualize them and pair them and understand that—[to borrow from] Afro-Caribbean philosopher Edward Gleason—what ties us together is actually our differences.

I think of Krasnow and I think also of Sister Corita Kent, who came from different spaces, but [they both] were seeking the sublime and trying to reflect the radiance of their spirituality and doing that through playing with letter forms and colors.

LM: I think about what you said about the differences pointing towards the same thing. Our individuality is the expression of a unique time and place and soul, but there is an idea of the patterns of human existence—the quest for the divine is one of those patterns, as is rebirth after death.

MFM: It can be found in a sacred text or it can be found in a flower, you know, in a sunflower. Or the light. You can find that same sublime nature in many different forms.

LM: Is there anything that I didn’t ask you or anything you’d like to ask me, that you’d like to talk about?

AC: To me, it was mostly that I wanted to capture—or, in my head, imagine—this person that was defiant. One of the things that to me is so telling about who he was is the fact that he came from a small place, a small city. He didn’t come from Paris; he didn’t come from London. He came from Ukraine, really kind of the corner of the world. Anyone that comes from a place like that, from a small town or from a remote place, when you end up in New York, you think the big lights of the city will impress you. But he just rejected it. To me that really is very telling about a person who really knew what he wanted. He understood the path he wanted to forge. I wanted to reflect that in a way. I think he was someone that understood the spirit of California, of Los Angeles. The city embraced him, and he embraced the city.

MFM: Is his studio or his home still there or is it gone?

LM: No, it’s now an apartment building. I won’t disclose the address in our interview for the sake of the residents who live there, but suffice it to say that it’s about three blocks north of the Costco on Los Feliz. That’s my landmark for Krasnow’s studio.

AC: That’s also a very LA type of thing to happen, you know, the most legendary places become some—you know—

LM: Anodyne stucco apartment building.

Whenever I go to that neighborhood, well, now I think about Peter Krasnow, but it really has its own energy and it has its own life. It’s a very distinct place in Los Angeles.

MFM: Being turned on deeper to Krasnow’s artwork is a treat. I already love Los Angeles, but it always makes me think even more highly of it. We’ve been doing this for a long time, you know, [being home to so many] creative people. But there are still these surprises and secrets. It’s the city that keeps giving.