< Return to main Chasing Dreams exhibition page…

During the research and development process of the exhibition Chasing Dreams: Baseball and Becoming American, I became totally enamored with pitcher and Los Angeles native Dock Ellis. Let’s be real—it’s hard not to like a man who drove a Cadillac originally intended for a Pittsburgh pimp (seriously, the car was abandoned at the dealership because the pimp was sent to jail) and who served as the sartorial inspiration for Bradley Cooper’s perm in the recent film American Hustle. You can check out Dock’s hair curlers for a perm he nicknamed “superfly,” in our galleries now until October 30, 2016.

Dock was the life of any party, but his irreverence and storied drug use have overshadowed the contributions he made to the game. Most know of Dock Ellis because he threw a no-hitter while high on LSD. Describing the experience in his own words, “[he] was high as a Georgia pine.” As the curator organizing the Skirball’s presentation of Chasing Dreams (the exhibition was originally developed by the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia), part of my job was to balance Dock’s narrative, to celebrate both his humor and his depth. A letter from baseball great Jackie Robinson, on view for the first time at the Skirball, helped us to explore that duality—in particular, how he, like Robinson, contributed to the struggle for civil rights.

While not a household name today, Dock Ellis was a bona fide superstar in the 1970s.The Pittsburgh Pirates had called Ellis up to the “show” in the spring of 1968 and by the end of the season, Ellis was an essential part of the Pirates’ starting lineup. He was selected for the 1971 All-Star Game, an annual event in July when the two branches of Major League Baseball, the National and American Leagues, join forces for one glorious game. Known for his big curveball and even bigger personality, Ellis commanded attention and had a knack for getting press. After the American League Coach Earl Weaver announced that he would start power southpaw Vida Blue during the All-Star Game, Ellis challenged National League manager Sparky Anderson to start him against Blue. He told reporters: “Ain’t no way they gonna start two brothers against each other in the All-Star Game … when it comes to black players, baseball is backwards and everyone knows it.” Anderson took the bait and started Ellis against Blue. The two men took the mound and made baseball history.

After Ellis’s All-Star Game verbal coup d’état, hate mail poured in. The press portrayed him as brash, unpopular, and erratic, and the letters pulsed with every ugly racial epithet imaginable. One letter threatened, “If you stick your head over the dugout, we’re going to shoot you.” But Dock Ellis wouldn’t be silenced; he defiantly stuck his head out high over the dugout during his next game. Outside of the spotlight, he lobbied congress to raise money for sickle cell anemia, and he spent two summers volunteering his time in a Pennsylvania prison.

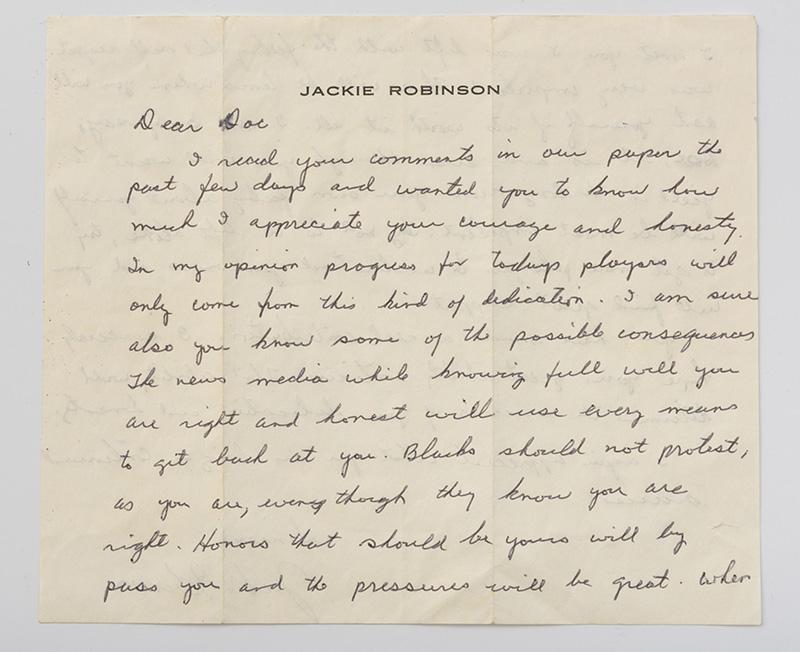

Letter from Jackie Robinson to Dock Ellis, 1971. Courtesy of Donald Hall Collection, Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library. Photos by Robert Wedemeyer.

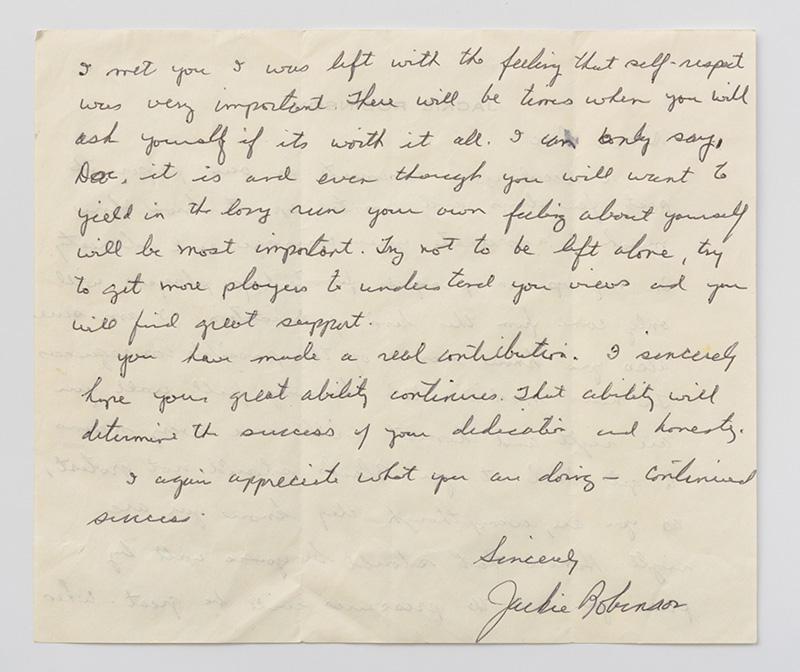

Back side of letter from Jackie Robinson to Dock Ellis, 1971. Courtesy of Donald Hall Collection, Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library. Photos by Robert Wedemeyer.

At this same time, Jackie Robinson’s health was failing; heart disease and diabetes were marching their way through his body, stealing his sight and strength. Nearly blind and mourning for his recently deceased son, Robinson took pen to paper:

I read your comments in our paper the past few days and wanted you to know how much I appreciate your courage and honesty. In my opinion progress for today’s players will only come from this kind of dedication. I am sure also you know some of the possible consequences. The news media while knowing full well you are right and honest will use every means to get back at you. Blacks should not protest, as you are, even though they know you are right. Honors that should be yours will bypass you and the pressures will be great. … There will be times when you ask yourself if it’s worth it all. I can only say, Dock, it is.

A little over a year after writing Ellis, Robinson was dead. Fall had set in over Brooklyn and the tree-lined streets grew thick with people as tens of thousands gathered to watch Jackie Robinson’s funeral procession on October 24, 1972. His autobiography was released shortly after his death; he titled the work I Never Had It Made: An Autobiography. Robinson’s title is as inspiring as it is pugnacious—a call to arms for players like Dock Ellis to continue fighting for access and respect. It is a fight that continues on fields and in streets, all across America. Towards the end of his life, Jackie Robinson was tired. He was sick and his heart was breaking, but he never stopped. He marched alongside Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and reached out to young players like Dock Ellis to remind them to stay the course, even when the path ahead seemed unbearable: “there will be times when you ask yourself if it’s worth it all. I can only say, Dock, it is.”